A small wildlife garden for towns and cities – and it’s really easy to maintain

This small wildlife garden is very pretty and easy to look after. Plus it attracts a wide range of wildlife.

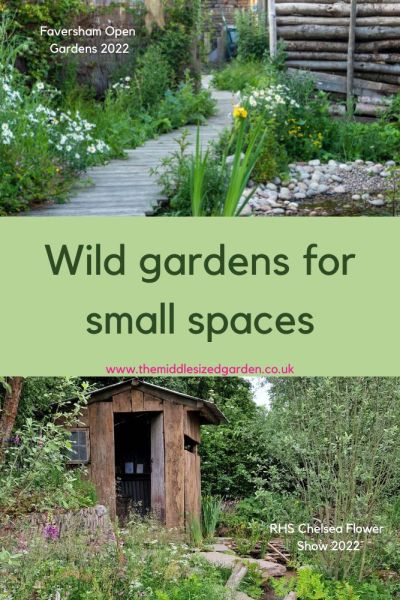

When the Rewilding Britain garden won Best in Show at the RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2022, it triggered a lot of debate in the gardening world.

Top picture of Anne Vincent’s wildlife friendly garden, open for Faversham Open Gardens & Garden Market Day 2022. The pic below it is of Lulu Urquhart and Adam Hunt’s Rewilding Britain garden, which won Best in Show at RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2022.

Is a small wildlife garden realistic, especially in a town? Would it be easy to maintain? And how managed does a garden have to be?

Anne Vincent’s garden, completed before RHS Chelsea 2022 hit our headlines, shows that it is practical to have an almost wild garden in towns and cities. She says that it is very easy to look after: ‘I really don’t do much gardening.’

And she also never buys plants, because she allows plants to colonise the garden rather than deliberately planting them. It is a very different approach to gardening!

The garden is around 60ft (18m) by 17ft (5m) and is in a street of terraced Victorian houses. It’s one of 30 garden open for the 2022 Faversham Open Gardens. Faversham Open Gardens is held on the last Sunday in June every year (25th June 2023, 10am-5pm) for Faversham Open Gardens & Garden Market Day.

Start with a pond

When Anne moved into the garden it was a blank canvas – just an oblong of lawn and a single old apple tree.

Anne Vincent’s garden when she moved in.

Anne’s son, Tom Joyce, was doing an environmental science degree and suggested that she turn the whole area into a small wildlife garden.

Anne Vincent’s garden now. The pond is a major feature, along with a raised deck path, a bog garden (on the left of the path by the screen), a shed and several other wildlife habitats.

‘My son told me I needed a pond,’ she says. ‘I expected him to dig me a small one at the bottom of the garden.’

However, Tom advised her that a larger pond would look after itself better. It would also host more species. He dug a pond that occupies approximately the first third of the garden. It’s about 20ft by 8ft, with a depth of around 2ft at its deepest point.

All ponds need to have access in and out. In a larger pond, this means you should create a ‘beach’ at one end, with different levels for different plants and wildlife.

Make sure there is easy access in and out of a pond. Here a ‘shallow end’ creates a beach, with pebbles and pond plants that prefer the margins. Safety note: babies and toddlers can drown in a few inches of water and won’t be able to get out of a pond on their own, so it’s important to make sure they don’t have access to any pond in your garden.

Tom fitted a rubber liner to the pond and added stones. Anne bought pond plants to stock it, concentrating on those which are native to the UK.

If you’re making a small pond out of a high sided container, then you’ll need bricks or stones inside, so that there is some shallow area. See this post to find out how to make a mini wildlife pond.

When I interviewed Helen Bostock of the RHS on gardening for biodiversity, she said that adding a pond is the best thing you can do for wildlife in a garden.

Fill the pond with rainwater if you can

If you fill your pond with rainwater, you’re less likely to get the algae and blooms that can cause problems in ponds, explains Anne.

The pond is filled by rainwater from the guttering. This reaches the pond via the downpipe, which has been extended beneath the deck to end up in the pond rather than in the sewage system.

Rain comes down the downpipe via the guttering on the house roof. The down pipe is extended under the decking to the pond, filling with fresh rainwater.

They also created a ‘bog garden’ overflow, running a pipe from the pond to the bog garden on the other side of the decking walkway.

In times of low rainfall, the bog garden can also be topped up from a water butt. ‘I don’t want to use tap water if I can help it,’ says Anne. ‘The chemicals in it would change the acidity of the bog garden.

Water butts often dry up in a prolonged drought, so have the largest ones you can fit in. Anne never waters her plants, so the water butt is only used for topping up the bog garden.

Think about the soil

Soil is a hugely important part of our eco-system, hosting a wide variety of worms, micro-organisms and funghi that are essential in the food chain.

The issue of how hard surfaces, such as concrete, stone, bricks or artificial grass, damage your soil health is a complicated one. There are many factors to consider when choosing what materials to use for paths and terraces in a small wildlife garden.

These include how porous a surface is (can rainwater drain away into the soil through it), whether worms and other creatures can emerge to breathe and also what happens to the material when it breaks down. Concrete, for example, leaches lime into the soil when it breaks down. Brick, especially old brick, is a useful ingredient in soil when it breaks down. Artificial turf doesn’t break down – it just wears out and has to go to landfill.

However, Anne has simplified her approach by using a raised deck outside the house and a raised deck path. ‘It means people don’t tread directly on the soil at all,’ she says. ‘And it creates a habitat under the decking. We’ve added stones that we found in the garden.’

The raised deck and walkway mean that people don’t tread on the soil, and it also creates a habitat beween the soil and the ground.

Generally, it’s now considered that digging is harmful to the soil and releases weed seeds. If you don’t want to go the full wildlife garden route, but would like to improve your soil with no dig techniques, see No Dig For Flower Borders here.

In order to avoid having any concrete on the soil, Anne has set the shed and waterbutt on a grid inset with grit.

You don’t need to buy many cultivated plants

Anne bought plants for the pond, but she hasn’t bought plants for the ‘border’ element of the garden. She did plant some wildflower seeds around eighteen months ago, but otherwise the plants in this garden have simply blown in on the wind or they’ve grown from seeds dropped by birds.

‘I have taken out a few plants that were becoming dominant,’ she says. But she has minimised even doing that. ‘For example, there was a lot of creeping buttercup at one point. I thought it might get invasive, but there seems to be a natural cycle. Other wildflowers arrived. They seem to keep the creeping buttercup under control.

When I visited, I saw oxeye daisies, wild carrot and pennyroyal in flower, along with some lovely purple thistle-type plants.

The oxeye daisies and wild carrot (Daucus carota) in this picture both blew in on the wind. Anne minimises any management of the border area, allowing plants to arrive and battle it out for territory. ‘It’s a very new garden,’ she says. ‘Last winter, I didn’t do anything to the plants at all, but this autumn I may strim them down. I’ll wait and see, though.’

Use native plants where possible

Wildlife have evolved to depend on the plants in their own locality. And plants grow best where they are perfectly suited to the conditions.

Anne bought native plants for the pond, although the oxeye daisies on the edge ‘found their way to the garden.’

And sometimes plants introduced from elsewhere take over the wild spaces, out-competing native plants which means that the wildlife that depend on them also fail.

So there is a strong case for using native plants, even in a small wildlife garden. Although where land is generally managed, such as in towns and cities, there’s much less chance of invasive plants escaping to the countryside.

Once again, this is a complex issue. Seeds and plants have been arriving in the UK via birds, the wind and trade routes for thousands of years. Wildlife has adapted well to much of it, and research by the RHS showed that pollinators benefited equally from both native and non-native flowers.

Some countries, such as Australia and North America, however, have had huge problems with the sudden introduction of non-native plant species.

As far as the UK is concerned, ‘native’ is generally defined as anything that was here before the last Ice Age. Plants that have been here for centuries are called ‘naturalised.’

You won’t necessarily find out if a plant is native from the label. But you can look it up on the RHS website. And there’s an extensive list of wildflowers native to the UK on the the Wildlife Trusts website.

And wherever you live, you can put ‘is x native to….’ into a search engine and find out.

Hedges and climbers are better than fences and walls in a small wildlife garden

Hedges and climbers offer food and shelter to wildlife. Walls and fences don’t.

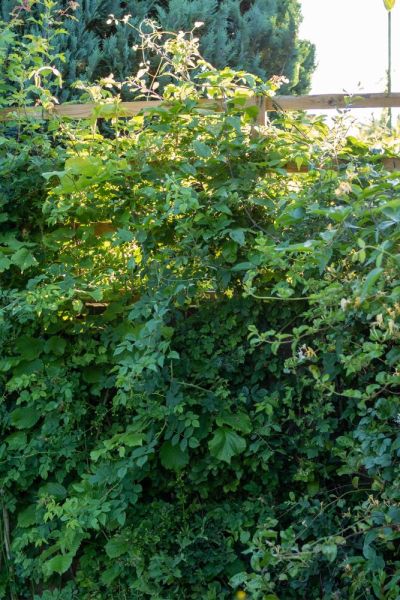

If you have a wall or a fence, you can make them more wildlife friendly by planting a hedge or climbers. Anne has done both. She planted native hedging, such as dog rose, hawthorn, blackthorn and wild cherry.

Anne planted these native hedging plants quite close together. There is some lovely blossom in spring and berries in autumn.

Think about having different habitat zones

Although Anne’s garden is quite small, there are various different habitat zones and she’s planning to add more. As well as the habitat under the decking, she has created a ‘hibernaculum’. This is a small covered area that can be accessed from the pond, where pond creatures can overwinter and shelter.

She’s added bark chips under the tree, and planted native ferns.

There’s a fernery under the tree, with native ferns and bark chips. A mature tree is hugely valuable to wildlife, so it’s always best to trim, prune or shape an established tree rather than cut it down.

There’s also an area of sand, where she’s planning a sand garden. ‘That’s an idea my son got from RHS Hampton Court one year,’ she says. ‘We’re going to create a sand dune, and see what likes growing there.’

Other good tips for a small wildlife garden

Anne’s garden doesn’t have grass or a lawn. If you do have a lawn, you can make it more wildlife friendly by turning all or part of it into long grass or a meadow. This post explains how to turn a lawn into a mini meadow. And if you’ve already done that, but are struggling to get the effect you want, here is Joel Ashton’s advice on top meadow lawn mistakes.

Joel also has advice for those thinking about making a few changes to become more wildlife friendly. His easy wildlife tips are here and there are more wildlife friendly tips in this post.

And Sally Nex also has tips on the three best things you can do to be more eco-friendly.

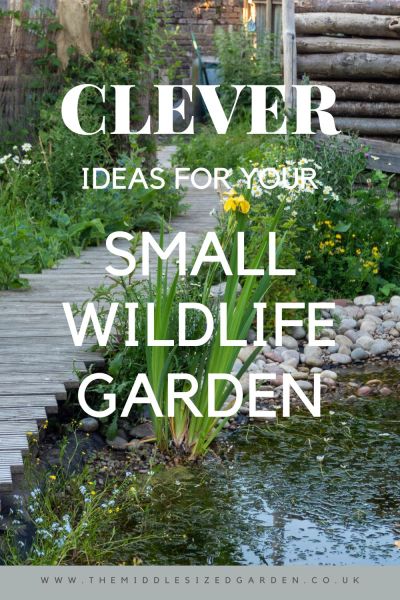

Pin to remember small wildlife friendly garden tips

And do join us for a free weekly email with more gardening tips, ideas and inspiration.

Love your garden transformation as I search for ideas for our small town space and 2 dogs! The lawn is doing well with dogs – how did your dog adapt to your new design?

Thankyou but this particular garden doesn’t belong to me – I was talking to Anne Vincent about her garden. Mine still has lawn, which is a help with our dog as he loves racing round it.

Unfortunately most uk town or city gardens are only half the size, it’s a shame no one showcases these modern postage stamp gardens

The average size of a London town garden is 140 sq metres, just about half the size of a tennis court, according to the Office of National Statistics. The average size for a town garden in the rest of the UK is 188 square metres and more in Scotland. This garden is approx 60ft x 17ft, which, converted to 18 x 5 metres, is 90 sq metres, so it’s a good bit smaller than the average UK town garden in size. However, statistics tend to be more accurate for about five years ago – I imagine the next set of statistics will see a smaller average size of UK town garden – but this one will probably still be slightly smaller than the average.

I love this idea, but it doesn’t work everywhere. I live on a 50 year old city lot in northwest washington state, similar climate to UK. I have planted many native plants, on property that has been lawn only (with landscape fabric everywhere else, with a lot of gravel). After 4 years, I am only slowing seeing my native garden come to being. I think the soil was poor, there is a lot of shade, and that awful landscape fabric with gravel on it (and more tree droppings on top of that) have made the soil pretty sterile. I am adding compost everywhere I plant things.

Yes, I agree that not all of the ideas work in all gardens – though it’s always good to see an extreme example to show us what can be done. Your garden sounds lovely.