Gardening for biodiversity – why changing the rules is good news for garden lovers!

Gardening for biodiversity means gardening with nature rather than trying to control it.

And it’s caused a revolution in our gardening rules. Firstly, it means less work for you.

A few years ago, you would have been advised to scatter slug pellets, take your leaves to the local tip and mow your lawns into smart stripes. You’d be expected to spray your plants against pests, dig your borders over and keep up a relentless programme of control against nature.

Now some of these jobs are considered unnecessary or even harmful.

The RHS garden spreads out across the horizon when viewed from RHS Hilltop, the new research centre.

And this isn’t some fringe or cult belief. This is coming from the leading gardening organisation in the UK, the Royal Horticultural Society. At their new research centre, RHS Hilltop, they are turning many gardening techniques and beliefs on their heads.

So I went to the RHS to talk to Helen Bostock, Senior Wildlife Specialist and Leigh Hunt, Principal Horticultural Advisor.

Anyone thinking that gardening for biodiversity means having an untidy garden will be reassured by this RHS Wildlife Garden at RHS Wisley. It is both a wildlife haven and a smart contemporary garden. Photo: RHS/Paul Debois

If you prefer to watch a video rather than read a post, you can see the full video interview here.

Why gardening for biodiversity matters

In the past, ‘getting rid of pests’ would have been seen as a separate issue from ‘how to make compost.’

However, Helen explains that if you get rid of certain pests, your compost heap may not work as well. ‘For example, if we didn’t have springtails (a small wingless insect) or composting worms, then our compost heaps won’t compost down as well.’

Springtails are sometimes called snow fleas. They’re more common in the US than the UK, where you can find lots of companies specialising in getting rid of them. Yet they’re not harmful to people, plants or animals.

‘And without slugs and snails, you wouldn’t have song thrushes,’ she adds. ‘So there are all sorts of knock-on functions that biodiversity performs within a garden. Without it, we’d really struggle.’

This contemporary sculpture by Tom Hare shows how gardening for biodiversity doesn’t have to mean looking scruffy. Inside, there are bug hotels and nesting materials, but to the passerby, it looks like a smart garden feature.

Slugs and snails also often eat dead leaves, so could be considered as tidying the garden.

The RHS is now discouraging the word ‘pests’ and officially discourages the idea that it is either possible or good to try to get rid of all snails, slugs and other insects. Instead of spraying, they suggest accepting a certain percentage of damage. And if you plant densely, so your garden is full of plants, you’re less likely to notice slug and snail damage.

Even a small space can make a difference

Helen says that a lot of species are struggling. More building means their habitats are fragmented. So there may still be places for them to live in parks, on railway banks or in a big garden.

But if the town is so built up that species can’t travel between them, a species of wildlife can be trapped in one place. This makes it difficult to breed in a healthy way. And it means that a pest or disease can wipe them out, because they can’t get away.

So if you garden for biodiversity in your front garden, balcony or pots, you can provide a vital stopover. It helps connect the bigger open spaces to each other. ‘Your little patch is part of the jigsaw,’ says Helen. ‘Things happen that put pressure on different species and they need to be able to move between spaces.’

Together, as gardeners, we control a good percentage of the open space available to wildlife. We can make a difference.

Front gardens, pots and patches of planting, however small, can offer enough food or shelter to allow wildlife to move from one area to another.

This post shows an example of a small town garden designed entirely to benefit wildlife and the environment. It’s easy to look after and very pretty.

Three simple things you can do

Helen says there are three simple things you can do

Add water

Adding a pond or water feature to your garden is the most important thing you can do to help wildlife.

Read how to create a mini wildlife pond out of a barrel or bucket here.

And if you’ve got the space for a larger pond, there are 11 garden pond ideas here.

Step one in gardening for biodiversity is to add water

Plant a tree

‘From a wildlife perspective, there’s a whole vertical dimension with a tree,’ says Helen.

Trees improve air quality, because they provide oxygen and absorb air pollution. They offer shelter and food for wildlife. Tree roots help stop soil erosion.

On a larger scale, trees encourage healthy rainfall. If a large area loses all its trees, it’s called deforestation. Deforestation is a major cause of creating deserts.

Read award winning garden designer Jamie Butterworth’s advice on choosing trees for a small garden.

And find out how to plant a tree correctly here. Tree supplier Majestic Trees estimated that over 80% of trees are planted wrong, even when they’re planted by professional landscapers.

Less mowing

‘If you have a patch of grass, go easy on the mowing,’ says Helen. This is probably one of the most revolutionary aspects of the new approach to gardening. Ten years ago, the RHS would have been telling gardeners how to achieve a smart, striped lawn.

Now Helen urges gardeners to ‘try something different this year. Leave a strip of longer grass around the edge, or a block in the middle.’

To see the difference, Helen suggests you hold off mowing for 4-6 weeks ‘to see if there’s something interesting in your lawn, such as clover.’ After all, this does mean less work for us gardeners.

What happens if my lawn is not mowed?

Some people are worried that leaving lawn grass long will wreck their lawn. But Helen says that allowing it to grow long for a few weeks won’t cause any permanent damage. The lawns at RHS gardens are often allowed to grow long and are then cut, as is her own garden.

We did No Mow May last year. The top photo shows how long the grass got after 28 days. The photo below it shows the grass after cutting. There are some browner patches, but we were several weeks into a hot summer drought at this point. I think our lawn looked a little less brown than some others in the area.

We did No Mow May last year. We allowed the lawn grass to grow long for 6 weeks from 1st May-24th June. We then went back to mowing. But we mowed every two weeks rather than weekly. Our lawn is far from perfect, but it’s fine. And it was less brown in the very hot summer, compared to other lawns locally.

A fully flowering meadow lawn isn’t necessarily easy to achieve, so I asked wildlife garden specialist Joel Ashton to help us correct typical meadow lawn mistakes here.

Are lawns bad for the environment?

Many people enjoy having a smart, green lawn and are happy to put a lot of work into it. There’s no doubt it looks good. And a garden with a smart lawn can be filled with wildlife-friendly borders, too.

Any lawn absorbs heat, pollution and carbon dioxide. Lawns slow water run-off in towns and cities, helping to stop flash flooding. And a lawn offers a habitat for worms and soil organisms.

At the heart of it, a lawn is lots of plants. And lots of plants are always better for biodiversity than the alternatives, such as concrete, stone or artificial grass.

However, if a lawn is regularly watered, fertilised and mown with a petrol mower, the resources it uses up cancels out most of the environmental benefits. However, worms, birds and soil life will still benefit.

When is a lawn a bad idea?

If you live in a part of the world where there are no native lawn or meadow grasses, you’ll need to work very hard to keep a lawn going. And it won’t offer much for your native wildlife.

That’s adds up to the chance that a lawn isn’t right for you. And it’s unlikely to be good for biodiversity either.

Much of the research calling lawns ‘green deserts’ has been done in parts of the world where an ‘English-style’ lawn has been introduced in a way that isn’t natural.

If your lawn needs a great deal of work to keep it looking good, then it’s probably time to reconsider.

But there are lots of different ways of having a lawn now. If you prefer a shorter, smarter lawn, try a robot mower or a mulching mower, both of which are more eco-friendly.

There are more options in this interview with lawn expert, David Hedges-Gower: how to achieve the right lawn for your style of garden.

Should you have mainly native plants in your garden?

Helen says that the RHS has recently done research to see if planting native plants in your garden is better for wildlife.

The principle is that native plants and wildlife have evolved to depend on each other. So, for example, bees that are indigenous to your area will want flowers that are also indigenous to your area.

The results of the study showed that the areas with native plants did support the highest percentage of pollinators and other insects.

But the areas planted with non-native plants also supported wildlife. And there was surprisingly little difference between the two.

Also the non-native plants offered flowers, berries and more earlier and later in the season.

Canna Wyoming is not native to the UK, but this sparrow very much enjoyed it. Award-winning photographer Molly Hollman was visiting my garden and captured him tucking in.

Helen also added that where you live makes a difference to the native plants issue.

If you back onto a nature reserve, moors or a coastline, it’s important to avoid planting anything invasive that might escape into the wild. But if you’re in a town or city, then it’s a very managed landscape. So non-native plants are less likely to be a problem.

And some countries have more vulnerable eco-systems than others.

Are double flowers bad for bees?

Double flowers are specially bred to have twice as many petals as ‘single flowers.’ They are layered, showy flowers. But it’s hard to see or reach any nectar or pollen, which makes them bad for pollinating insects.

I asked Helen if we should aim for a particular percentage of pollinator-friendly single blooms.

‘I don’t like to be too prescriptive,’ she says. ‘If you have a small space, think about having some pollinator-friendly flowers. But if your garden is larger, then you’ll probably naturally plant a mix.’

Helen says that she herself loves double roses. So she plants a mix of single and double roses. The single roses are good for pollinators and make lovely rose hips for the birds. But even the double flowered roses help wildlife. ‘They are useful for my leaf cutter bees,’ she says.

Although single flowered blooms offer nectar and pollen for pollinators, double flowered plants may offer benefits to wildlife in different ways.

Tolerate (some) pests in your garden

Leaf cutter bees take small circles out of leaves. But the RHS says that this doesn’t damage the plant. And the bees help with pollination. ‘They’re a valuable part of garden wildlife. They should not be controlled.’

However, sometimes there can be new pests or diseases that can disrupt the healthy growth of plants. For example, the box moth caterpillar has devastated box plants.

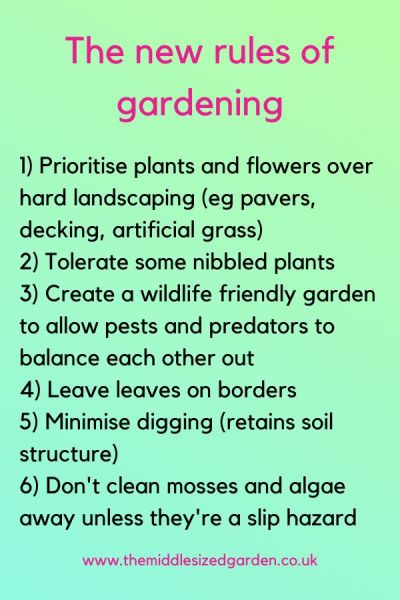

Gardening for biodiversity has changed the rules of gardening

The RHS no longer consider snails and slugs to be ‘pests’ because they have an environmental value in the garden. To find environmentally friendly ways of keeping them off your plants, read slug resistant plants – the easy way to beat snails and slugs in the garden. And because dahlias are particularly vulnerable, here is Keep Dahlias Free of Earwigs, Slugs & Snails Without Chemicals.

What damages biodiversity in a garden?

I asked Leigh Hunt, Principal Horticultural Advisor at the RHS, what damages biodiversity in our gardens.

He says we shouldn’t feel too guilty. After all, we’ve often inherited garden features from previous owners.

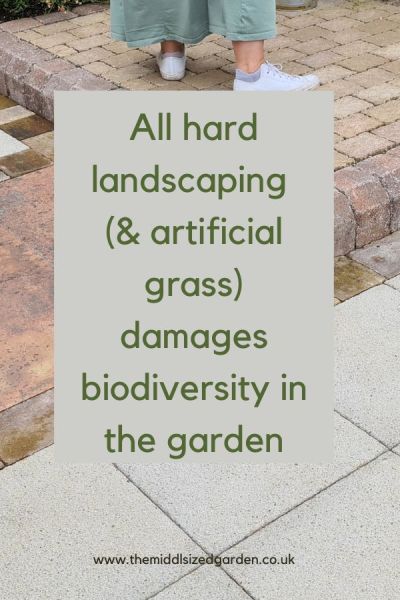

But the key is to reduce the amount of hard landscaping you have. Leigh suggests replacing a fence with a hedge or growing climbers up a wall or a fence.

If you have a large space that is covered with concrete or paving, can you reduce it by a small amount? For example, if you have paving or concrete for parking, you can’t park in corners.

In the RHS’s sustainable gardening tips, they say that if the UK’s 30 million gardeners each pulled up one paver in their gardens and planted it up, the environmental benefits could be as much as the equivalent of heating one million homes a year.

Minimise hard landscaping to help biodiversity. Even pulling up one paver and planting it up can offer environmental benefits.

Different ways of creating a beautiful biodiverse garden

There are lots of different ways of incorporating biodiversity into gardens. For example, this is a small town garden which was created to be as wildlife friendly as possible.

And this is a rented garden, where the tenant had no control over the hard landscaping. He succeeded in creating a wonderfully wildlife friendly garden in pots.

There’s an increasing interest in the importance of maintaining soil structure by not digging. Find out how No Dig makes flower borders easier to manage and weed-free here.

The RHS has answers to frequently asked questions about wildlife here.

Pin to remember gardening tips for biodiversity

And do join us. See here for a free weekly email with more gardening tips, ideas and inspiration.

I’m in the US but was drawn here by your beautiful photos. But, don’t you need mostly native plants to support the caterpillars that I assume your birds need to feed your young? This is why Prof. Tallamy has advocated for natives here; I would assume the same would apply for the UK and anywhere else.

The situation (and indeed the definition) of native plants is very different in different parts of the world. In the UK, a native plant is one that was here before the last ice age (33,000 years ago!), so as you can imagine, there is a somewhat limited range. For the US and Australia, a ‘native plant’ is one that was there before western colonial settlement (ie around 500 years ago). The other issue is that Europe, including the UK, is joined by land mass or relatively crossable waterways to Asia and Africa, so there’s been thousands of years of continuous trade and migration across the continents. Much of our wildlife has adapted, often gradually. However, the last 500 years has seen a very hasty introduction of a wide number of different plants to the more isolated continents of America and Australia, and that’s been much harder for wildlife to adapt to, hence the importance of encouraging people in the US and particularly Australia to plant natives. However, anywhere where there is a changing climate does also need to think about providing a wider range than just native plants – for example, here our bees enjoy salvias, which offer pollen and nectar when most of our ‘native’ flowers are over. I think even professors sometimes need reminding that there’s no ‘one size fits all’ when it comes to answering nature’s problems and that change is a natural part of the life cycle – it’s when it is too fast that so many of the problems arise.

I live in a cul-de-sac with very tidy neighbors so I keep my front lawn reasonably short but let my back garden lawn grow. I think it looks nice with a tidy edge.

Good point!

I knew some of this but needed inspiration to actually start doing it . Thank you for being the stimulus to give me courage to help support the planet in my own small way. Ive been thinking of letting my grass grow for a long time but with your support I am actually going to do it. Many thanks

I hope you enjoy it!