Are you embarrassed by your Latin plant names skills?

Do you avoid using Latin names for plants? Do they seem too complicated or even unnecessary?

After all, we can all have beautiful gardens without knowing the Latin names of our plants. So I try to pretend I don’t know the proper plant names. And I also try to pretend that this is OK.

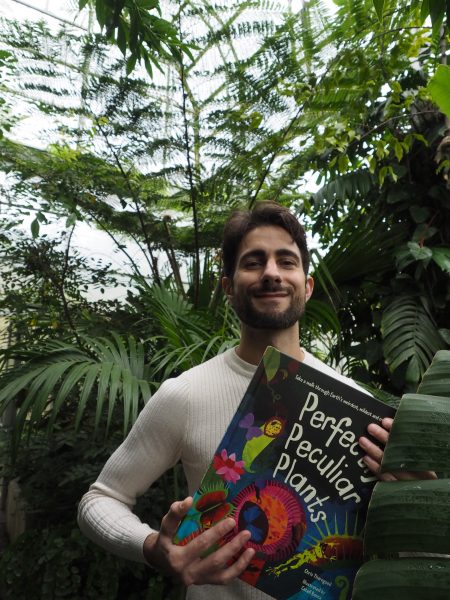

I’ve just been sent a children’s book called Perfectly Peculiar Plants by Dr Chris Thorogood (Quarto £12.99) of the Oxford Botanic Gardens. And the plants in it have their Latin names.

Dr Chris Thorogood and Perfectly Peculiar Plants at the Oxford Botanic Gardens.

If children can manage Latin plant names, I thought it was time we amateur gardeners got a grip of them. So I went to the Oxford Botanic Gardens to ask Dr Chris Thorogood to explain them.

(note: links to Amazon are affiliate, which means you can click to buy and I may get a small fee, but it doesn’t affect the price you pay. Other links are not affiliate.)

What are Latin names for plants?

Firstly, they aren’t necessarily Latin names, says Chris. ‘Some of them are Greek. Strictly speaking they’re called the ‘scientific names’ of plants.’

In this post, I’m (mostly) sticking to the phrase ‘Latin plant names’ because it seems to be the phrase that most of us use.

Chris says he included the scientific plant names as well as the common ones in his book because it would help children become familiar with the fact that such names exist.

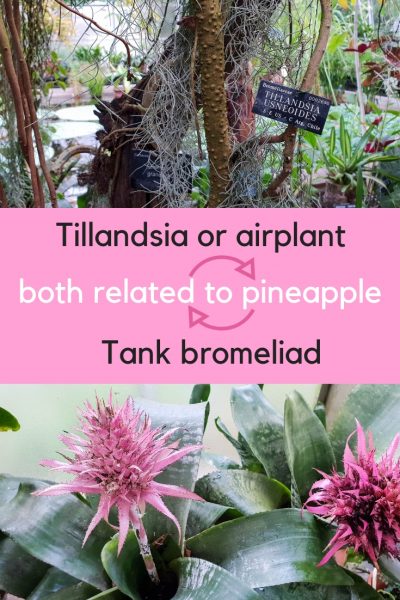

This is the Tank Bromeliad or Aechmea zebrina. Other Bromeliacaea include pineapples and air plants.

‘Up to 1 in 5 plants worldwide is at risk of extinction, so it’s essential to enthuse the next generation of botanists. When people think of conservation, they commonly think of pandas and tigers – I want to show children that plants are just as extraordinary.’ Understanding the names of plants is part of that.

Why do we need Latin plant names

Before Karl Linnaeus devised the current plant naming system, plants were given lots of different names across different languages and culture.

‘We use plants for medicines, food and horticulture, so it’s important that we know what plant we’re talking about in order to use it and grow it consistently,’ says Chris. ‘It helps to make sense of the seemingly chaotic diversity of living things.’

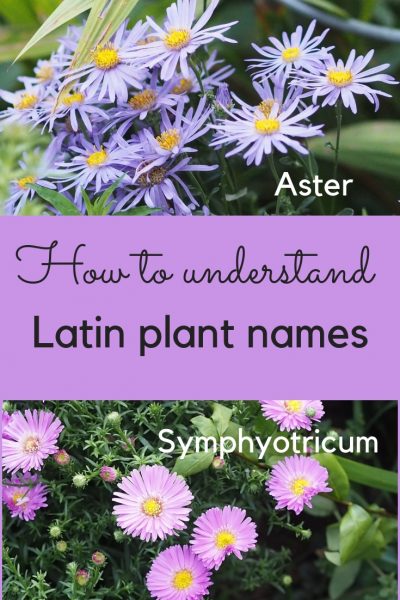

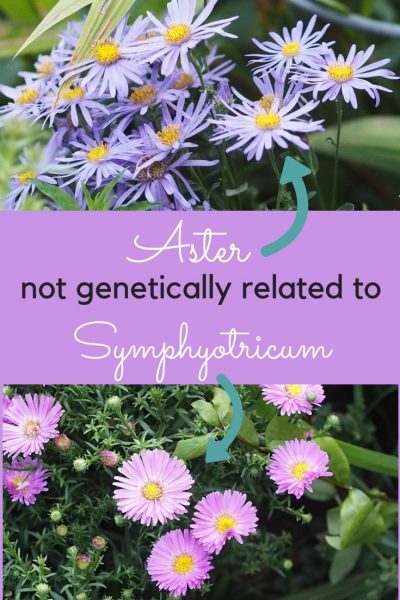

For example, ‘Michaelmas daisy’ is the common name for a number of different and entirely unrelated flowering plants. We used to call them ‘asters’, but botanists discovered that although they looked alike, many weren’t related genetically at all.

The top flower is Aster mellus ‘King George’. For many years, the pink flower beneath (Symphyotricum novi-belgii Heinz Richard)was also considered to be an ‘aster’ but DNA testing has shown that it is no relation. Yet the common name of both is ‘Michaelmas daisy.’

This doesn’t matter if all you want is a beautiful plant in your garden, but it would be critical if you discovered a medicinal or food use for Michaelmas daisies.

For example, begonias…

I became interested in Latin plant names when I interviewed plant-lovers in their own gardens. Philip Oostenbrink, Head gardener of Canterbury Cathedral and Dan Cooper, blogger at The Frustrated Gardener. When I asked what a plant was, I often got the answer ‘Begonia luxurians‘ or ‘Begonia Martin Johnson…..’

Begonia ‘Martin Johnson’ in Dan Cooper’s study. It’s the plant with the blue and purple leaves and jagged tips.

Begonia sutherlandii on my mantelpiece….you wouldn’t initially think that both my and Dan Cooper’s begonias were related….

None of these begonias looked like the begonias I’ve seen for sale in garden centres or used in pot displays. How big is the begonia family, I wondered? It reminds me of a friend of mine who has 45 first cousins. When there’s a wedding her side of the church is entirely taken up by relations.

My begonias from Great Dixter: Begonia ‘Burle Marx’,’Garden Angel Blush’, Begonia carolineifolia, Begonia sutherlandii, Begonia scharffii, Begonia luxurians

So I bought six begonias at the Great Dixter Plant Fair. They all look very different from each other, and some are very different from pot begonias. But they are all related. And they have lots more cousins….

Now that’s what I call a begonia. Begonias(unknown varieties) seen in a pot display this summer.

How Latin plant names work

Back to the Oxford Botanic Gardens… Chris explains that Karl Linnaeus devised a system known as ‘binomial nomenclature’. That translates as ‘two names’.

‘The first name is the generic name of the plant. For example, a banana palm is Musa. And the second name is the specific branch of it,’ says Chris. ‘So I’m standing next to a Musa ornata or Ornamental Banana Palm. These are written in italic.’

You would definitely want to know that you were buying pineapples, airplants or tank bromeliads….especially if you were shopping for supper….Bromeliads are another big plant family.

Then there are further varieties, often cross-bred deliberately to create better yields of vegetable or more beautiful garden plants. These names come after the generic and specific names, and are called ‘cultivar’ or variety. For example, I have an Aster mellus ‘King George’.

So it’s like our system of identifying people by using first names and family names, only in reverse. I suggested to Chris that if he were a plant, he might be called ‘Thorogood Chris Dr.’ Or written: ‘Thorogood Chris ‘Dr”.

How to write Latin plant names

The first two names are written in italics, with a capital letter for the generic name. Any cultivars or variety after that is in standard text with capital letters if necessary (ie ‘Martin Johnson’).

A fun present for a future generation of botanists?

Although Perfectly Peculiar Plants (Quarto £12.99) is aimed at 8-12 year olds, I felt I learned alot from it. It would be a great present for anyone wanting to interest their children in botany, conservation or gardening. And if you enjoy reading aloud to children, I think it would work for children younger than eight, too.

There’s a fuller interview with Dr Chris Thorogood on this video:

The Oxford Botanic Gardens and Arboretum are the oldest botanic gardens in Britain. They’re open every day, with a series of lectures, workshops and tours, and over 6,000 plants.

It’s a pleasure to see such beautifully shaped and cared-for trees.

The Oxford Botanic Gardens are a green heart right in the middle of Oxford – check for different opening hours in winter and summer.

Dating back to 1621! The Oxford Botanic Gardens & Arboretum…a delightful place to visit.

The Middlesized Garden blog is published every Sunday morning, so do join us. And do subscribe to the Middlesized Garden YouTube channel which uploads every Saturday.

Pin for reference